The other night, I participated in the Providence Pub Sing, hosted by Armand Aromin and Benedict Gagliardi (The Vox Hunters) in Providence, RI. As Halloween was approaching, there was especial demand for songs of ghosts and other spooky matters, and since I always look for an opportunity to sing, at this time of the year, one of my favorite ballads, “Tam Lin,” I offered that (with the indulgence of the participants, since it does not offer much participation). I learned this song from the singing of Frankie Armstrong, an extraordinary English singer of traditional songs whom I had the great fortune to hear several times at the Philadelphia Folk Festival in the early 1970’s. The version I sing is hers, as is the way I sing it, as she was a great influence on my own singing. At the same time, I’ve been singing this song for decades now, and have not listened to her recording of it for at least 20 years, so I may have introduced some minor changes. With that caveat, here is the version that I’ve been singing, and which I sang the other night:

Tam Lin

(Traditional; Child no. 39)

Lady Margaret, Lady Margaret, a-sewing of her seam,

And she’s all dressed in black,

When a thought come to her head, she’d run into the wood,

And pick flowers to flower her hat, me boys,

And pick flowers to flower her hat.

So she’s hoisted up her petticoats a bit above her knee,

And so nimbly she’s run o’er the plain.

And when she’s come to the merry green wood,

She’s pulled the branches down, me boys,

She’s pulled the branches down.

Then suddenly she spied a fine young man,

Stood underneath a tree,

Saying, “How dare you pull these branches down,

Without the leave of me, Lady,

Without the leave of me?”

She said, “This little wood, it is me very own.

My father gave it me.

And I can pull these branches down,

Without the leave of thee young man,

Without the leave of thee!”

He’s taken her by the lily-white hand,

And by the grass-green sleeve.

And he’s laid her down at the foot of a bush,

And he’s never once asked her leave, no,

And he’s never once asked her leave.

And when it was done, she’s turned herself about,

To ask her true love’s name.

But she’s nothing heard, and nothing saw,

And all the wood grew dim me boys,

And all the wood grew dim.

Now there’s four and twenty maidens, all in the court,

Grown red as any rose.

Excepting fair young Margaret.

As green as glass she goes, she goes,

As green as glass she goes.

Then outen spoke the first serving girl.

She’s lifted her head and smiled.

Saying, “I think me lady’s loved too long,

And now she goes with child, she goes,

And now she goes with child.”

Then outen spoke the second serving girl.

“Oh, and alas,” said she.

“I think I know a herb in the merry green wood,

That’ll twine the babe from thee, Lady,

That’ll twine the babe from thee.

Then Margaret’s taken up her silver comb,

Made haste to comb her hair.

And away she’s run to the merry green wood,

As fast as she could tear, me boys,

As fast as she could tear.

But she hadn’t plucked a herb in that merry green wood,

A herb as any one,

When by her stood young Tam Lin

Saying, “Margaret, leave it alone, alone,

Oh, Margaret, leave it alone.”

“Oh how can you pluck that bitter little herb,

That herb that grows so gray,

To take away that sweet babe’s life,

That we got in our play, me love,

That we got in our play?”

“Oh, tell me the truth, young Tam Lin,” she said

“If an earthly man you be?”

“I’ll tell you no lies, Lady Margaret,” he said.

“I was christened the same as thee, Lady,

I was christened the same as thee.”

“But as I rode out one cold and bitter morn,

From off my horse I fell,

And the Queen of Elfland, she took me

In yon green hill to dwell, to dwell,

In yon green hill to dwell.”

“But tonight it is the Halloween,

When the elfen court must ride.

So if you would your true love win,

By the old mill bridge you must bide, me love,

By the old mill bridge you must bide.”

“And first will come the black horse, and then come by the brown,

And then come by the white.

And you’ll hold it fast, and fear it not,

And it will not you affright, me love,

And it will not you affright.

“And first they will change me, all in your arms,

Into many a beast so wild.

But you’ll hold me fast, and fear me not.

I’m the father of your child, you know,

I’m the father of your child.”

Then Margaret’s taken up her silver comb,

Made haste to comb her hair.

And away she’s run to the old mill bridge,

As fast as she could tear, me boys,

As fast as she could tear!

Then in the dead hour of the night,

She’s heard the harness ring,

And, oh, me boys, it chilled her heart

More than any mortal thing it did,

More than any mortal thing!

And first come by the black horse, and then come by the brown,

And then raced by the white,

And she’s held it fast and feared it not,

And it did not her affright me boys,

It did not her affright!

The thunder roared across the sky,

And the stars they blazed like day!

And the Queen of Elfland gave a thrilling cry,

“Oh young Tam Lin’s away, away,

Oh young Tam Lin’s away!”

And then they have changed him all in her arms,

To a lion that roared so wild!

But she’s held it fast and feared it not,

‘Twas the father of her child, she knew,

‘Twas the father of her child.

And then they have changed him all in her arms,

Into a loathsome snake.

But she’s held it fast, and feared it not.

It was one of God’s own make, she knew,

It was one of God’s own make.

And then they have changed him all in her arms,

To a red hot bar of iron!

But she’s held it fast, and feared it not,

And it did to her no harm, me boys,

And it did to her no harm.

And the last they have changed him, all in her arms,

Was to a naked man,

And she’s flung her mantle over him,

And cried, “Me love, I’ve won, I’ve won!”

And cried, “Me love, I’ve won!”

Then outen spoke the Queen of Elfenland,

From the bush wherein she stood,

Saying, “I should have torn out your eyes, Tam Lin,

And put in two eyes of wood, of wood,

And put in two eyes of wood!”

After I had finished, Molly Bledsoe Ellis came over to the table where I was sitting, and asked why I sing that song — or, more specifically why do I sing it that way, as it includes an instance of rape (verse 5), followed by the implication that the victim takes the perpetrator to be her “true love” (verse 6). I could only respond that I sing it that way because that is the way I learned it. I recognize that the depiction is problematic, but many of the old songs we sing have such problems. I do not condone all of the acts that take place in the songs that I sing. She suggested that lines could be changed to rid the song of the offending acts, and I responded that it is sometimes difficult to do that while still preserving the substance of the song, but I would take a close look at it. The issue provoked a long discussion, and we sang very few songs after that. But it was a good discussion, with most people feeling that it is a very important issue, but also with some feeling that songs need to be preserved as they’ve come to us, warts and all.

I might also add that while I sing mostly traditional songs, I am not a traditional purist. I do sometimes make small changes to songs, to “improve” them (at least in my mind). I have also made changes that respond to just the issue raised. For example, I sometimes sing the song “Hang Me, Oh Hang Me,” a song about an outlaw who complains that he would rather die than rot in some prison cell. Some versions of the song tell what some of his crimes were, but the one I sing does not. The version I learned, however does have a verse that goes: “Lulu, oh Lulu, open up that door, before I have to open it with my old 44.” I take these lines to be very typically referring to domestic violence. She fears him, and does not want to let him in, while he threatens to break in, with a gun. I do not sing that verse, and I think the song is just fine without it. I might also note that the late Utah Phillips, a great songwriter, never performed one of his more famous songs, “Rock Salt & Nails”, because it was written in anger in his younger days, and implies violence against women.

So I promised that I would take a serious look at the song to see how some words might be changed to remove the problematic issues while still preserving the substance of the story. At first, I did not think it would be easy. The substance of the song, as I take it, is that Margaret meets Tam Lin while picking flowers in the wood. Tam Lin tells her that she needs his permission to pick the flowers, and she responds that the wood was given to her by her father, so she does not need his permission. With that, Tam Lin responds by raping her, but then promptly disappears when she turns “to ask her true love’s name.” She then becomes pregnant, and one of her serving maids advises her of an herb that would cause an abortion, and she rushes to the wood again to find it. There, Tam Lin appears again, and tells her not to pick the herb, presenting another problematic line: how can she “take away that sweet babe’s life, that we got in our play?” She then asks who he is, and he tells her that he was a human, but was kidnapped by the elf queen, and made a changeling. But he also tells her that it is Halloween, and the elf court will make an appearance, presenting the opportunity for her to rescue him, if she can seize him when he passes (as a horse), and hold on to him through many trials. This she does, as he is changed from a horse to a lion, a snake, a red hot bar of iron, and finally to a naked man.

Now I have long seen this tale to be a metaphor for giving birth. She has been impregnated by a person she does not know, considers aborting the child, but eventually goes through with the birth — the trials she faces representing her difficult labor, finalized by her holding in her arms a naked man (the child), whom she covers with her mantle and cries “I’ve won!” Tam Lin is both the father and the child. That is simply my interpretation, but I do see some essentials here: she meets Tam Lin, has an argument with him, and then is impregnated by him. It is standard belief these days that rape is not so much a sexual act, as an expression of power and violence, and that follows from the argument, which is why I thought it might be difficult to turn the sex act into one of consent. Nor did I see how one could simply leave out the sex act altogether, as my own interpretation of the song depends on her being pregnant.

So I began by looking at the various versions of the song in Francis James Child’s The English and Scottish Popular Ballads (Boston: Houghton & Mifflin, 1882-1889; reprinted by Dover Publications, 1965). “Tam Lin” is Child no. 39, and he presents 10 versions in volume 1, p. 335-358, with the 10th in the “Additions and Corrections,” p. 507-508. It was interesting to see that versions A and B both lack the offending verses, although their place is taken by a line of asterisks, which as far as I can see are unexplained. My assumption is that these verses were left out in the original publications that Child drew from because of their scandalous nature. Both versions have her become pregnant, but there is no explanation of how. Version C has no pregnancy at all. Version D has the song much as my version goes, with the verses:

He took her by the milk-white hand, And by the grass green sleeve,

And laid her low down on the flowers, At her he asked no leave.

The lady blushed, and sourly frowned, And she did think great shame;

Says, “If you were a gentleman, You will tell me your name.”

He tells her his former name as well as the present name he carries in the “fairy court”, and the verse about the herb follows immediately:

“So do not pluck that flower, lady, That has these pimples gray;

They would destroy the bonny babe That we got in our play.”

Version E has no sex act and no pregnancy. Version F has a thinly implied sex act and a resulting pregnancy. Version G has the rape, much as in my version and Version D, along with the later verse that mentions the “bonny bairn That we got in our play.” Version H does not have the sex act, but like A and B, has a row of asterisks where the verses might be. Version I has an interesting take:

He’s taen her by the milk-white hand,

Among the leaves sae green,

And what they did I cannot tell,

The green leaves were between.

He’s taen her by the milk-white hand,

Among the roses red,

And what they did I cannot say,

She neer returnd a maid.

So, here there is no implication that the sex act was non-consensual, even though it follows the earlier argument between the two characters. Version J is a mere fragment, and has no relevance.

I did some looking about online to see what I might find, and came upon this fine website, all about the ballad. The site contains analysis of many different versions, and prints those versions, including all of the Child versions, as well as those sung by Frankie Armstrong, Fairport Convention, Steeleye Span, Ewan MacColl, Ann Briggs, Anais Mitchell, and many others. So I will do no further analysis here.

What I will do is to suggest a change that would rid my own version (or Frankie Armstrong’s version) of the offending parts without harming the substance of the story. One might simply substitute the verses from version I, so we have:

She said, “This little wood, it is me very own.

My father gave it me.

And I can pull these branches down,

Without the leave of thee young man,Without the leave of thee!”

He’s taen her by the milk-white hand,

Among the leaves sae green,

And what they did I cannot tell,

The green leaves were between.

He’s taen her by the milk-white hand,

Among the roses red,

And what they did I cannot say,

She neer returnd a maid.

And when it was done,

she’s turned herself about,

To ask her true love’s name.

But she’s nothing heard, and nothing saw,

And all the wood grew dim me boys,

And all the wood grew dim.

But this makes one wonder how they got from the argument over who has power over the wood to having a consensual sexual act. I would like to have some sort of transition there, and perhaps it can come from the fact that she explains that she owns the wood. That might make him realize who she is, when he had not recognized her until then.

Then you must be Lady Margaret,

If this your forest be,

And I have long been in your thrall.

Would you come and lie with me lady,

Would you come and lie with me?

He’s taken her by the lily-white hand,

And by the grass greensleeve,

And they’ve lain among the flowers bright,

Upon a bed of leaves, me boys,

Upon a bed of leaves.

I am currently in the process of recording some of my favorite songs, and have already recorded Tam Lin, but I will go back into the studio and redo this one, with the new verses. They may change slightly before that happens. Meanwhile, if you do not mind hearing the original version, there is an older recording on this very website, under the Music tab.

I find this an acceptable change to make to the version that I sing, especially given the variation in the other versions I’ve found. It does not solve the problem as it exists in many other songs. The problem is a historical one, and in fact it persists today. In some places, it is still common to force a rapist to marry his victim. It is a problem that stems from seeing women as property, and applying the rule that if you break it you own it. Another song that I have sung, “The Knight and the Shepherd’s Daughter,” is about just that. It tells the tale of a young woman out walking who is raped by a passing knight. She follows him to the king’s castle and tells the king what happened. The king responds that, if she can identify the culprit he will mete out the appropriate punishment. If he is married, he will be hanged, if he is single, he must marry her. She does identify him, and “wins” her case by forcing her rapist to marry her. I have not sung this song for a long time, and I don’t see how I could “fix” it. She is already the “victor” in the story, but it is a Pyrrhic victory. These songs come down to us from times that had very different ideas of morality, equality, and many other things. We preserve them for the sake of some of the qualities they have, and in spite of some of the others. On the other hand, I will continue to sing one of my favorites, “The Outlandish Knight,” which is a standard murder ballad turned inside out when the young woman tricks her would-be murderer and kills him instead. I do not condone killing but can approve of it in self-defense. Moreover, the irony is seductive, especially when he asks her to save him from drowning, and she responds:

Lie there, lie there, you false young man!

Lie there instead of me!

It’s six foolish maids have you drowned in here.

Go keep them good company!

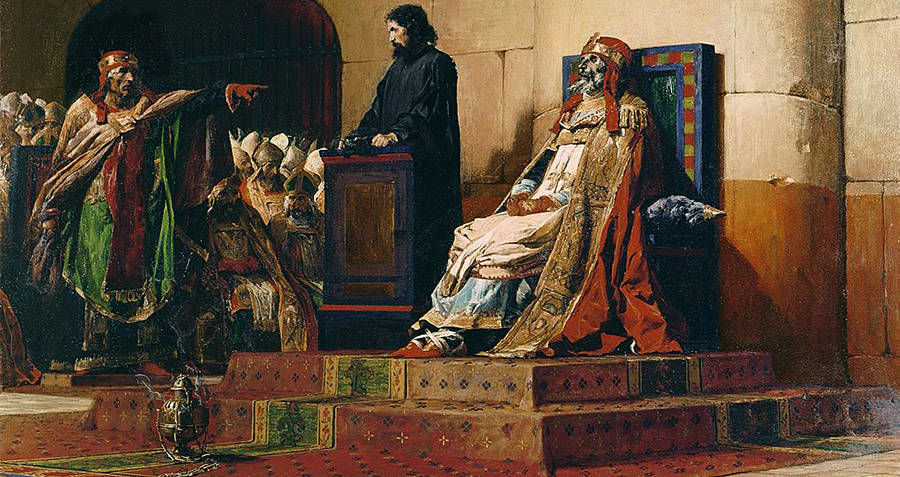

Painting: Zazněná (Bemused), by Wilhelm Bernatzik, 1898. (Brno, Moravskie Galerie Brno)